Allocators double down on 'Big Four' UK equity funds; Levering up in a low-return world

Welcome to Asset Allocator, FT Specialist's newsletter for wealth managers, fund selectors and DFMs.

Forwarded this email? Sign up here.

Strong get stronger

Last spring we highlighted how just four strategies dominate UK equity fund selection. Today, more than a year on, our fund selection database show wealth firms have doubled down on these preferences – despite UK equities falling further from favour in the meantime.

UK shares have had plenty thrown at them over the past 15 months: Brexit, a general election, and now a pandemic. With sentiment having taken a series of hits – interrupted only by a brief period of post-poll excitement in December - the typical DFM’s exposure to domestic equities is lower than it was last March.

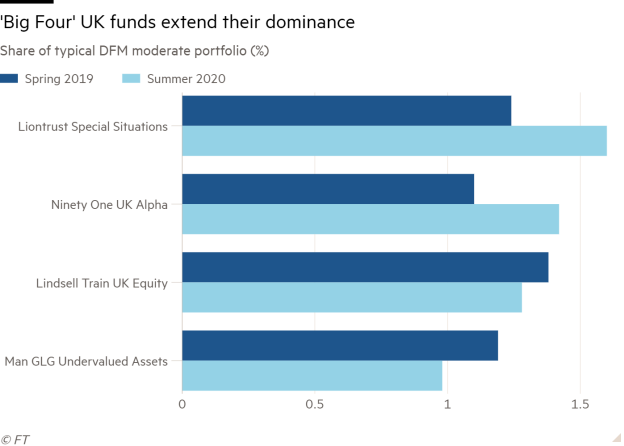

More often than not, that’s been brought about by allocators cutting satellite positions and doubling down on their main holdings. As a result, the four funds in question – Lindsell Train UK Equity, Liontrust Special Situations, Ninety One UK Alpha and Man GLG Undervalued Assets – have solidified their place at the top of the fund selection charts.

As of last March, these funds accounted for 38 per cent of all UK active growth fund picks in DFMs’ moderate portfolios. Today, that figure has risen to 42 per cent.

Some trends have shifted slightly: a combination of more buyers adding Liontrust to their portfolios, and a slight shift away from Lindsell Train’s quality growth preference, has seen the former become the most popular UK strategy, as the chart below shows.

With the market trends of yesteryear largely intact, buyers who’ve stuck by both these funds, as well as Ninety One, have been rewarded: all are top quartile again in 2020.

That leaves Man GLG. Despite its name, Undervalued Assets isn’t the most out-and-out value strategy ever devised. But its tilt in that direction, coupled with a significant stumble in the year-to-date performance charts, has seen its popularity dwindle slightly. Whether it will be replaced in the top four is another question: its nearest challenger, Polar Capital Value Opps, has similar issues to deal with at the moment.

Levers to pull

Uncertain times unsurprisingly mean that leverage is largely off the menu for allocators. Sentiment may have improved materially over the past quarter, but lines in the sand are more distinct than they were last year. The likes of investment trusts are still being marked down in most selectors’ eyes in the event they remain highly geared.

Set against this attitude is the need to meet performance targets in an increasingly low-return world. As we discussed yesterday, wealth firms may see the current moment as that rare occasion where clients will accept a reset moment. But not all investors will be so fortunate.

Institutions, for instance, will be all-to-aware that their obligations haven’t changed. That’s already prompting some to turn to riskier assets more forcefully. Plans in train at Calpers, the largest public pension fund in the US, could see leverage account for as much as 20 per cent of the fund’s value.

Questions abound. The fund’s 7 per cent annual return target looked ambitious even prior to the arrival of a global pandemic: to some it may now feel improbable. Clearly it’s this target, rather than a careful assessment of the underlying opportunities, that's prodded the fund to look at levering up.

True, many allocators will view a move into illiquid assets as a decision that nonetheless makes investment sense – particularly as pension funds aren’t as burdened with the problem of liquidity mismatches.

But Calpers’ past record in managing its alternative assets raises some red flags, even if the returns themselves were impressive. So too does this reminder from one of its own board members. Still, there is a wider application here: many of these arguments are unique to pension funds, but the risk/reward equation is becoming ever harder for investors of all stripes.

On the out

Will the fallout from Wirecard’s fall from grace do more damage to active managers’ collective reputation? Few funds in the UK still held the stock as of last week – but then few managers held the kind of company in which Neil Woodford invested prior to his downfall. The similarity here is that a high-profile manager, in this case Alexander Darwall, has been left severely exposed.

There are plenty of differences – this episode won’t prove a fatal blow for Mr Darwall – but it has already been interpreted as another blow to active investment in general. This has now been confirmed as a particularly egregious case of sticking with a stock for too long, and/or of refusing to believe in warning signs. But even retail investors will know that blow-ups are part and parcel of stock picking. And whatever their aversion to particular funds as a result of events like these, it’s a risk the majority will still be happy to take once more with a different manager.